Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD)

The Doubting Disorder: A False Promise of Safety That Leads to A Life of Captivity

What is OCD?

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is a mental health condition that’s characterized by unwanted, intrusive thoughts (obsessions) and repetitive behaviours or mental acts (compulsions) that people find difficult to control.

People struggling with OCD perform compulsions hoping to reduce their anxiety. But also, in the belief that these actions will prevent a catastrophe or feared event from happening, even though these actions are not realistically connected to the outcome. For example, someone might believe, "If I check each electrical appliance three times, then I’ll keep my family safe from a fire." And find themselves repeatedly doing behaviours like this to keep themselves and others safe.

It's like OCD is trying to solve a problem that isn’t a problem…but ‘could be’ a problem. And this possibility, even 1 in a million, is intolerable and causes distress. This is why OCD is known as the ‘doubting disorder’ or likened to a bully.

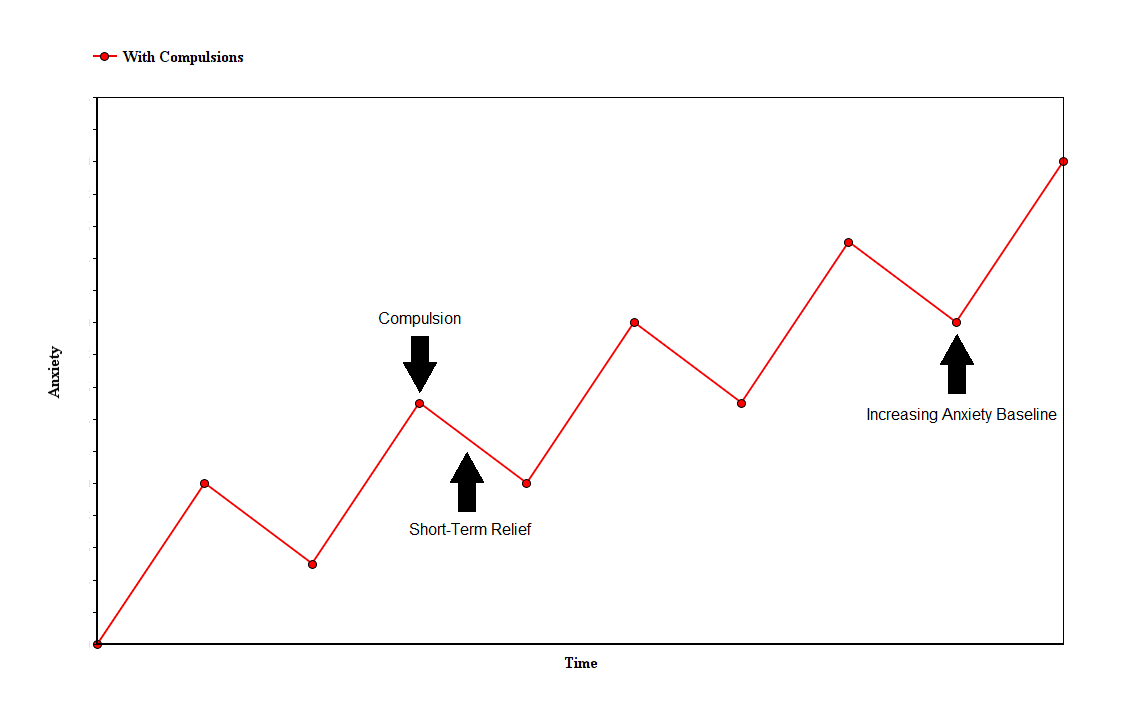

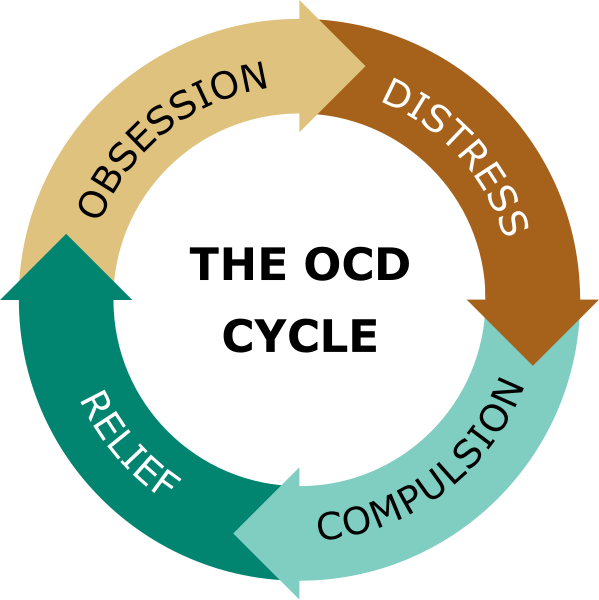

Although compulsions provide short term relief, they reinforce the false belief that the ritual prevents harm, trapping the person in a cycle of anxiety and repetitive behaviour. This cycle worsens over time, increasing distress and making it harder to break free.

Features

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) is defined by two interconnected symptoms: obsessions and compulsions. The relationship between these two cause anxiety.

Obsessions are unwanted, intrusive thoughts, images, or urges that cause intense distress and anxiety. These can include fears of contamination, doubts about causing harm, or intrusive thoughts about taboo subjects such as violence, sexuality, or religious blasphemy. For example, a person may fear that they are a risk to others, so become very anxious about being in public. These thoughts are distressing and persistent.

Compulsions are repetitive behaviours or mental acts that people with OCD feel driven to perform to reduce the anxiety caused by their obsessions (this is called ‘neutralising’) or to prevent a feared catastrophe. These compulsions can include behaviours, such as checking locks repeatedly, washing hands excessively until the skin becomes raw, or arranging objects to feel “just right.”. Or using the before example, someone may avoid public situations if they feel they are a risk. Or seek reassurance “I’m a risk to others…so I’ll ask my friend if I’ve did anything wrong”. With no amount of reassurance ever being enough.

Compulsions can also be mental, such as silently repeating words, counting in specific patterns, or mentally reviewing past actions to ensure no mistakes were made. Some compulsions, like constant reassurance-seeking from loved ones, may seem subtle but can significantly impact relationships e.g., putting pressure on a partner to behave in the ‘right’ way. As a partner may feel they are helping by offering reassurance (as is a natural thing to do!) but this can reinforce the compulsive behaviour.

Despite providing brief relief, compulsions ultimately trap individuals in a vicious cycle of anxiety and ritualistic behaviour.

While there are many different types of OCD (e.g, contamination OCD, Relationship OCD, Harm OCD, Pure-OCD to name a few), they often fall into five main themes:

Checking, contamination, symmetry and ordering, ruminations and intrusive thoughts, and hoarding.

Checking behaviours involve repeatedly verifying that actions, like locking doors or turning off appliances, were completed correctly. Contamination fears drive compulsions like excessive cleaning, which may escalate to avoiding public spaces altogether. Symmetry obsessions lead to rituals such as arranging items in a particular order or performing tasks an exact number of times. Ruminations involve becoming trapped in cycles of obsessive thinking, often about existential or philosophical questions. Hoarding, while distinct from OCD, can be linked when driven by fears of making a catastrophic mistake in discarding items.

A lesser-known aspect of OCD is the belief that thinking about an event increases the likelihood that it will happen (known as ‘thought action fusion’). For example if I have an intrusive thought about my child becoming ill, then this means they are likely to become sick.

There is also a tendency toward an exaggerated sense of responsibility, with people feeling that they must take extraordinary measures to prevent harm or protect themselves or loved ones. In therapy you see this manifest through people being hyper critical of themselves, and viciously criticising themselves if they make mistakes.

Part of the reason why OCD is so debilitating is the self-reinforcing nature of the problem. Compulsions, although performed to ease anxiety, really sustain it by reinforcing the false belief that rituals prevent harm. The temporary relief they provide convinces individuals to repeat the behaviour whenever distressing thoughts return. This creates a never-ending loop where the ‘solution’ becomes the core of the problem.

Misconceptions & Issues

Many people use the term ‘OCD’ casually as a personality quirk to describe someone neat and tidy. While these comments are often innocently said with no bad intentions, they misrepresent what OCD actually is.

OCD is not a personality quirk.

OCD is a serious mental health condition that causes immense distress and can severely disrupt a person’s daily life. Misusing the term OCD in casual conversations not only reinforces harmful stereotypes but also contributes to stigma, which can contribute to those who suffer feel misunderstood and isolated. In therapy, I often speak with people who have attempted to open up about their experiences for someone to minimise OCD impacts, or not understand how distressing it can be. Or even sometimes say “Oh my friend has that…” and go on to tell a funny story.

Another common misconception is that OCD is just about cleanliness or being neat. The mental side of things (the obsessions) are often over looked as people just see the compulsions.

While compulsive cleaning can be a symptom, it is usually driven by intense fear, like the fear of contamination, rather than a preference for tidiness. As an example, someone with OCD may believe, “If I don’t clean the counter, I could touch it, and germs might harm my family.” Their behaviour is not about enjoying a clean environment but the anxiety caused by the urges, and trying to reduce overwhelming anxiety and the false belief that cleaning will protect their family. OCD is more than cleaning, and can take various forms e.g., anxiety about ones sexual orientation, religion, relationships, real events.

Another common myth is that people with OCD enjoy performing their rituals or find comfort in them. But most individuals are painfully aware that their compulsions are irrational and unhelpful (at least adults are, not always with children). However, they feel trapped in a distressing cycle where performing the compulsion is the only way to briefly relieve intense anxiety caused by intrusive thoughts. Far from providing satisfaction, these rituals often feel exhausting, time-consuming, and isolating, leaving people feeling like prisoners to their own minds.

Many also mistakenly believe that people with OCD can “just stop” their compulsions if they try hard enough. This misconception stems from a misunderstanding of how the disorder operates. For some people, their urges are as uncontrollable as the air they breathe, no matter how much they try they just feel like they can’t stop.

The compulsive behaviours associated with OCD are not habits that can be easily broken—they are powerful responses to severe anxiety. Although overcoming OCD often involves resisting compulsions, this process is extremely difficult and distressing, especially without professional support.

You don’t have to control your thoughts. You just have to stop letting them control you

Impacts

OCD can affect nearly every aspect of a person’s life, from education and career prospects to relationships and family dynamics.

Some individuals may be visibly trapped in compulsions for hours, making it difficult to leave the house or manage daily responsibilities. Others may suffer internally, appearing to function normally while battling severe anxiety and distress from intrusive thoughts.

I’ve worked with people who struggle to maintain steady employment, as their compulsions or intrusive thoughts consume hours of their day. At home, relationships with partners, parents, children, and friends can suffer due to misunderstandings, tension, or the isolating nature of the disorder. Sometimes people come to therapy and share their heartbreak at hiding these experiences from loved ones. These hidden struggles can cause significant strain in relationships, especially when loved ones unknowingly become entangled in the disorder. Family members may find themselves constantly offering reassurance, avoiding certain topics or places to prevent triggering anxiety, or even participating in rituals e.g, such as taking out the rubbish in a specific way or helping a loved one avoid perceived contamination.

The physical consequences of OCD-related compulsions can also be severe. Excessive hand-washing can lead to raw, bleeding skin, while repeated checking behaviours including inspecting locks or appliances can cause physical strain or even injury. The mental distress of living with OCD can sometimes lead individuals to self-medicate with alcohol or drugs.

How is OCD Diagnosed?

OCD is diagnosed through a thorough evaluation of a person’s symptoms, focusing on the presence of distressing obsessions and compulsions that interfere with daily life. The process usually begins with a visit to a GP or healthcare provider, who may refer the individual to a mental health specialist for further assessment.

Diagnosis typically involves a clinical interview, where the healthcare professional explores the nature, frequency, and impact of obsessive thoughts and compulsive behaviours. Standardized tools, like the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), are often used to measure the severity of symptoms and how they affect daily functioning.

These assessments help healthcare providers determine whether the symptoms meet the criteria for OCD and rule out other conditions with similar features. The diagnosis process is crucial for developing an appropriate treatment plan, which can significantly improve the individual’s quality of life.

Getting Support

For people struggling, remember that you are not alone—and that recovery is possible. The first step toward getting help is often speaking with a healthcare professional, such as a general practitioner (GP), who can assess symptoms and refer individuals to a mental health specialist.

OCD recovery looks different for everyone. For some, it’s an ongoing journey; for others, it may feel like reaching a destination. A crucial part of this process is believing that recovery is possible. The path is rarely linear and deeply personal, but with appropriate support, individuals can learn to manage their symptoms and regain their sense of control.

The most effective support for OCD often includes therapy, sometimes combined with medication. While medication doesn’t "cure" OCD, it can be a helpful tool—especially for those experiencing severe symptoms or for whom therapy alone hasn’t been enough. A GP or psychiatrist can provide guidance on medication options and monitor their effectiveness.

Talking openly with a mental health professional, such as a Therapist or Psychologist, in a safe and non-judgmental space can be a powerful step toward understanding the disorder and breaking free from its grip.

Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT), particularly a form called Exposure and Response Prevention (ERP), is the most researched and recommended form of support (*other supports are available*).

In ERP, individuals intentionally expose themselves to anxiety-triggering thoughts or situations (exposure) while resisting the urge to perform compulsive behaviors (response prevention). Over time, this process helps retrain the brain to tolerate discomfort and reduces the anxiety linked to obsessions. For example, someone with a fear of contamination might be guided to touch objects they perceive as "dirty" without washing their hands afterward—first with the support of a therapist, then in self-guided practice.

This process can be challenging and anxiety-provoking, but research shows it is highly effective in helping individuals recognize that their fears don’t come true and that their anxiety naturally decreases without compulsive behaviors.

Beyond therapy, support groups and peer networks can offer valuable encouragement, reducing feelings of isolation by connecting individuals with others who share similar experiences.

Some useful organizations to include:

Organisations:

- https://www.ocduk.org

- https://www.ocdaction.org.uk

- http://www.ocdsymptoms.co.uk

- https://www.ocdforums.org

I’ve written two free booklets about OCD which readers may find helpful:

OCD recovery isn’t a straight path—it requires patience, resilience, and self-compassion.

No matter how much theory or how many tools are available, OCD can still feel frightening, exhausting, and overwhelming at times. But no one has to face it alone. Help is available, and recovery is possible.

Getting Started

To arrange an appointment, you can email me at andrew.kidd@firstpsychology.co.uk or contact the First Psychology Services Team on 0141 404 5411.